Food for thought

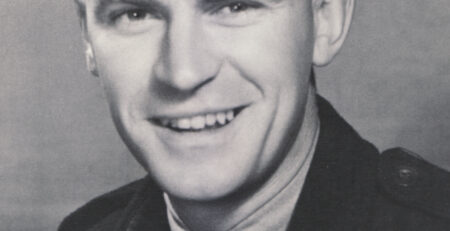

Old boy Ed Halmagyi, better known as TV chef Fast Ed, made a science-themed cooking show especially for Trinity students learning remotely during Science Week.

And though he taught them how to make a delicious chicken saltimbocca, students also watched a separate streamed Science Week lecture on the diet of the future, in which meat as we know it is likely to be replaced to some extent by the ‘cultured meat’ familiar to vegetarians and vegans.

Ed, the chef, author, and media host renowned for his work on Channel Seven’s Better Homes And Gardens, touched on many subjects during his Trinity culinary special, including botany, history, language (saltimbocca translates from Italian as ‘jump into the mouth’) and the science of microwave food radiation.

But for hungry boys in lockdown in late 2021 it may have been difficult to concentrate on anything but the mouth-watering flavours paraded before them.

Ed’s three-course meal included an entrée of Sicilian-style gnocchi and a chocolate pudding dessert, with all courses featuring native Australian ingredients.

While the pudding was cooking in a microwave oven, Ed explained how microwaves work, using non-ionising radiation at a frequency designed to affect just one substance – water.

It causes water molecules to vibrate, producing friction and thus heat.

He also tackled the issue of healthy eating, explaining that while too much fat is not a good option, some fat is essential because it helps the body absorb vitamins.

His chicken saltimbocca, wrapped in slivers of prosciutto (or “grown-up bacon” as he called it) was accompanied by baby carrots and a history lesson.

He explained how the orange carrots we are all familiar with today never existed once upon a time. They were produced by crossing red and yellow carrots to create the orange in honour of the 400th anniversary of Dutch nationhood.

The chicken was infused with South Australian saltbush leaf, mountain pepper leaf from the ACT, and Tasmanian native pepper berry, coated in a butter and maple syrup sauce, and glazed with Marsala.

His poached gnocchi, made from buffalo milk ricotta, was flavoured with Australian aniseed myrtle instead of fennel seeds, and accompanied by parmesan, spinach leaves, pine nuts, and a sauce of butter, lemon zest, and wattle seeds.

His trademark sense of humour was never far from the surface.

“What does it taste like?” he asked. “As someone who works on television, if it’s wrong, I just tell you it’s good.”

“This is all made in next to no time,” he told students.

“It brings together the best of traditional cooking with indigenous ingredients, and along the way you have learned a few bits and pieces about science as well.

“I hope some of you will be inspired to have a crack at making this at home.”

By all accounts that is exactly what happened.

Secondary sciences teacher Alastair Hunt thanked Ed for being so generous with his time.

He said students also made their own bread and ice-cream at home during Science Week.

“We had some great plans but being in lockdown prevented House cooking competitions and consuming new food items such as insects!”

The prospect of a diet without traditional meat was also canvassed in a streamed Science Week lecture by food scientist Avani Bhowjani of Marrickville-based biotech company Vow Foods.

She explained how the current production of meat was inefficient, requiring nine calories of feed input to make just one calorie of meat, in the case of chicken, or a whopping 25 calories in the case of beef.

She also explained how meat production contributed to greenhouse gas emissions and deforestation, as well as draining the world’s water resources.

To produce just half a kilo of meat required 115 full bathtubs of water, she said, at a time when 2.1 billion people did not have access to safe drinking water.

Australia was the world’s second largest consumer of meat per capita, she added, explaining how ‘cultivated’ or ‘cultured’ meat is made outside an animal’s body.

Scientists take a biopsy the size of an almond which enables them to isolate stem cells which mimic the body’s ability to produce muscle, tissue, and fat.

Refinements to taste and texture meant that cultivated meat had come a long way since 2013, when the first beef burger was made without cows.